Warning: Undefined array key "dirname" in /home/anapuafm/public_html/wp-content/themes/anapuafm/include/plugin/filosofo-image/filosofo-custom-image-sizes.php on line 133

Warning: Undefined array key "extension" in /home/anapuafm/public_html/wp-content/themes/anapuafm/include/plugin/filosofo-image/filosofo-custom-image-sizes.php on line 134

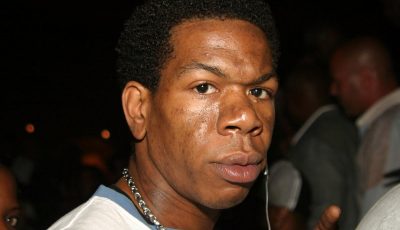

Insight into Rapper Craig Mack’s final days and the “cult” that he joined

Craig Mack faced a fight-or-flight moment before leaving his family, rap career and demons behind in New York.

The artist behind the platinum 1994 hit “Flava In Ya Ear” was gunning to end someone’s life in 2011 but chose another path, he revealed in an interview filmed weeks before his death on March 12.

“I had a gun in my lap and I’m sitting there talking to God, saying like, ‘I don’t want to do this, but if it comes to getting ugly with somebody going to try to kill me, I’m going to have to do something first to prevent that,’” Mack said in footage shared with the Daily News.

Mack, whose memorial is Wednesday at the Faith Baptist Church in Hempstead, L.I., looked to a car radio for solace during his breakdown.

He flipped through AM stations looking for the hip hop channel he loved while contemplating whether or not to use the weapon. Instead, he found Ralph Gordon Stair — a self-proclaimed prophet — preaching on the airwaves.

“I knew that it was God talking to me because of the way it made me feel emotionally,” Mack said. “I broke down crying all over the place in the car: ‘I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m sorry I was thinking about trying to do this to somebody.’”

“It was really in my heart to kill him. I was going to do it,” Mack said.

According to Mack’s account, he called the controversial religious leader for help and found the salvation he was looking for. He flocked to the Overcomer Ministry in Walterboro, S.C., and told only a handful of friends and family of his decision. The rest of the world learned of his new home, panned by former parishioners as a cult, when a startling video of Mack denouncing his life of “wickedness” surfaced in 2012.

Last year, Mack, no longer the young man behind the hit that launched Sean (Diddy) Combs’ Bad Boy Entertainment in 1994, urged his friend and former producer, Alvin Toney, to come to Walterboro.

Most of Mack’s life story was familiar to Toney. Toney produced the single that earned Mack a Grammy nomination, and the “Get Down” and the “Project: Funk Da World” records that followed. Those records now hang above Toney’s desk at his Midtown office.

The producer also watched Mack grapple with being denied a second chance with the acclaimed hip-hop label, believing he was eclipsed by Combs’ other star, the Notorious B.I.G.

“I think that was something that bothered him a lot,” Toney said.

“He just wished he had more time to show the world who he was,” the producer said. “He was cut short of it.”

The Mack who Toney found at his modest home in Walterboro wanted to share a life story that rivaled Biggie Smalls and Tupac Shakur, both of whom reached massive success and fame before being shot dead. Mack’s decision to leave New York in 2011 was motivated by the growing fear he could meet a similar fate to the legendary rappers.

“If I would have stayed, then I’d be dead, too,” Mack said in the February interview.

Toney declined to reveal who Mack had considered killing but suggested the conflict was set off by “emotional things” involving his family.

In the footage, Mack said he was abandoned as a newborn on a Bronx street. He was adopted five months later to a family who raised him in Suffolk County. He stayed out of trouble as a kid by fine-tuning a knack for words with the Long Island rap community.

Toney recorded several hours of interviews with Mack at his home in mid-February. By that point, Mack was acutely aware that he was dying, struggling to breathe and relying on a cane to walk.

He passed away four weeks later of heart failure at age 46.

Mack’s last interview will be the subject of an upcoming documentary featuring Long Island rappers Biz Markie and both members of the EPMD hip-hop group, Erick Sermon and Parrish Smith.

Despite fielding years of late-night phone calls from Mack, Toney admittedly ignored the depth of problems at the rural church until he reviewed the footage his team recorded.

“When I was down there and I talked to Craig, I didn’t think it was a cult,” Toney said.

Even Toney’s Prime Time Music partner, Vincent Digregorio, agreed that the music mogul was blind to Mack’s misplaced devotion in Walterboro.

“I think that Alvin was trying to believe it wasn’t a cult,” Digregorio said. “But yeah, it was a cult. As much as he didn’t want to believe that his friend was down there and in a cult.”

Toney eventually concluded his friend had been had, lured to the troubled compound by Stair’s apocalyptic broadcasts.

“I’m angry because there’s ways he could have went about giving himself to God,” Toney said. “I don’t think that was the right place for him because I knew how good his heart was and I think they played on his good heart.”

For most of Mack’s final seven years, he lived alongside dozens of parishioners who had been similarly drawn to the church. According to Colleton County records, Mack bought a home from the Faith Cathedral Fellowship — the nonprofit branch of Stair’s church — for $5 in November 2017. He lived there until his death but remained an ardent follower of 84-year-old Stair, even after the minister was charged with criminal sexual conduct, criminal sexual conduct with a minor and burglary in December.

The victims, some of whom were minors at the time of the alleged attacks, claimed Stair molested or raped them in the radio room where he delivered his sermons, according to local reports. In 2002, Stair was accused of raping two women at the church and pleaded guilty to lesser charges of assault and battery.

Toney was aware of the latest round of accusations ahead of his road trip to South Carolina and confronted Mack about the sexual misconduct claims for the documentary.

“Your preacher just got arrested … for having sex with a 12-year-old. How do you take that?” Toney recalled asking Mack.

“He said, ‘I will forgive him because we forgave the people that killed Jesus,’” Toney said. “At that point, he was all in.”

Family members who were with Mack the week of his death in South Carolina, declined to comment on the documentary or his life with the Overcomer Ministry.

“It’s not my story to tell,” said Andrew Mack, Mack’s brother.

Mack was buried on the church property, according to Erick Purvis, Prime Time Music’s manager.

The purpose of Toney’s documentary, which started as an attempt to pull back the curtain on Mack’s lost talent and unpublished music, shifted as he realized the extent of the church’s role in Mack’s life.

“I want everybody to understand what a cult is, what a real church is and what hip-hop music is,” he said.

That hold had no apparent impact on the surprisingly secular music Mack wrote and recorded during a burst of inspiration in his final months. He penned a handful of songs, according to Toney, including one that asked the same question fans were clamoring to know after his sudden death.

These are lyrics from one of Mack’s unpublished songs:

“Hey, Mr. Governor. New York is melt down so stand in the background.

State of emergency. Martial law. Call the National Guard because ya’ll did that before.

Here comes the baddest emcee. You all know the status about me. Time to accept the fact that the game wasn’t doubled and along came Mack.

Craig Mack, I need you, baby.

Craig Mack, where the hell have you been?

Craig Mack, we need you, baby.

DJ, play the record again.

Get them up. Set it on fire, baby.”

The lyrics were set to Biggie’s 1995 “One More Chance” remix.

Source: NYdailynews